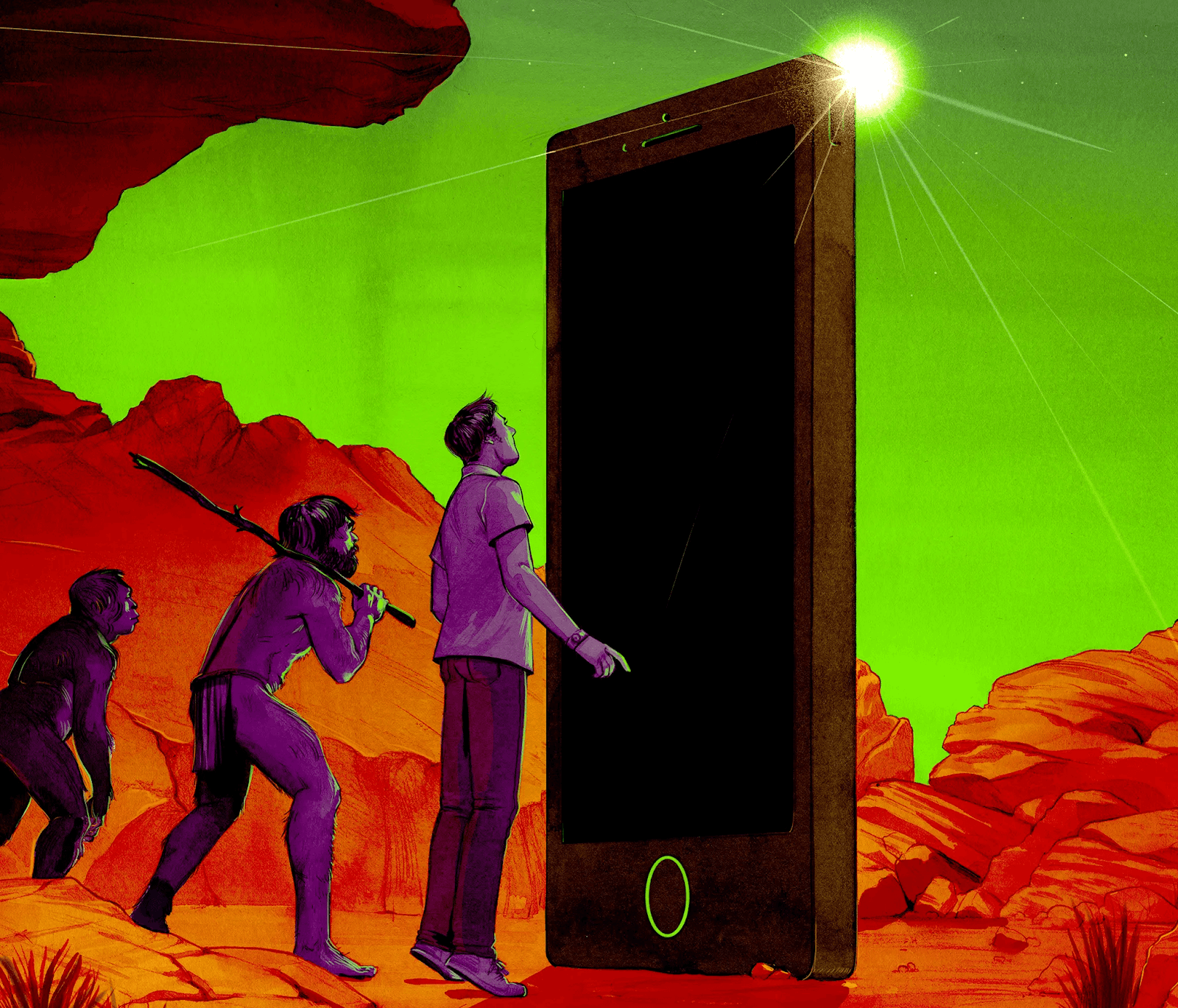

The False Promise of Progress - Essay

What is progress?

From childhood, the notion of progress meant a world or a society moving toward less poverty, fewer diseases, more education, greater freedom of expression, and so on. I bet you also had a similar understanding of the word progress. But now that I have grown older and witnessed certain types of progress, they didn’t align with my original understanding of the word.

As a kid, I asked a lot of questions, so my parents told me I should aspire to become a scientist. I spent my time chasing that dream. Then, I hit my teenage years, and something happened. I was out in the world, going to school and classes by myself or with friends, and the reality of our society started to chip away at my perception. The rose-tinted glasses were losing their tint. Naturally, I asked: Why is this the case? Why are people suffering all around me?

As I progressed through life, I kept asking questions, and although I didn’t get answers, I was handed a solution. I was told by so-called experts in the media that if I studied science, then engineering, and became an engineer in the technology sector, I could change the world for the better. I could help. Of course, I didn’t blindly accept it—they provided evidence. Evidence of how modern technology has helped the world and how it has personally benefited me.

So, to recap: As a kid, I asked too many questions and was told I should aspire to become a scientist. Then, when I started seeing how broken our society is and asked why, instead of receiving an answer, I was given a solution—with proof.

Eventually, I graduated with my engineering degree and became an engineer in the tech sector. My first job, as you may expect, was not about changing the world—but I was too naive to know that. I told myself that maybe this wasn’t the right fit, so after a few years, I switched. Then I switched again.

Throughout this whole process, I realized that something wasn’t working—this was not what I had set out to do. And so, I dug into the questions that had remained unanswered from my childhood and teenage years. Very soon, I started finding answers.

I studied subjects like media studies, sociology, and political science—fields that I had been told were pointless, less valuable, and unimportant by the educational institutions in my country. Eventually, the pieces started falling into place, and everything made sense.

The reason was simple: Only a certain type of progress is allowed—the kind that makes money. More specifically, the kind that makes the rich even richer, giving them more power to dictate our lives—what food to eat, what to wear, what is considered beautiful, which gods to worship, and so on. There is no money to be made in alleviating poverty; in fact, the rich would lose if that happened—so it’s not allowed.

Tell the kid who asks too many questions to study science, because a questioning child studying humanities and social sciences is dysfunctional to the establishment. Why automate jobs that involve cleaning drains and sewers? Those workers don’t cost much and aren’t a threat. Instead, eliminate the engineers—they get paid the most. Silence the writers and activists—they are a threat to profit.

Tech bros are hell-bent on automating art because art has a tendency—and some might argue, a function—to be rebellious. Automate the engineers because they take the highest salaries, instead of automating the jobs that are the least human.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I am not saying science hasn’t done good; it has fundamentally changed our world and improved so many aspects of our lives. But—and there is a but—science is not the same as technology, and not all technology is good or equal. And no, technology is not a benign tool; some are outright evil, like nuclear weapons and weapons in general. Their sole purpose is to kill—and kill humans—because, last I checked, we don’t need more advanced weapons for protection from animals, as weapons a few decades old are quite good at that job.

The more I dug, the clearer it became. The problem was never a lack of innovation, intelligence, or even resources. It was that progress—real progress—was not profitable. It does not serve the interests of those in power. A world without poverty, without oppression, without manufactured scarcity would mean a world where they lose control. So they feed us a different kind of progress. One that convinces us that a new iPhone every year, AI-generated content, and billionaires colonizing Mars are signs of advancement while millions go hungry, healthcare remains a privilege, and war is a business.

They tell us to chase progress, but only the kind that keeps the machine running. They tell us to dream, but only within the lines they have drawn. And if we dare to think beyond that, if we dare to ask why, they dismiss us, silence us, or worse, convince us that there is no alternative.

But there is. Progress should not be measured by how fast our processors are or how many companies have reached a trillion-dollar valuation. It should be measured by how much suffering we have alleviated, how many lives we have improved, how much freer, kinder, and fairer our world has become. And if that kind of progress is not profitable, then maybe it’s time we stopped measuring everything in profit.

Because real progress is not what makes the rich richer. It’s what makes the world better.